Minority Report #1

By Alexis Buss, Industrial Worker (July 2002)

For the past few years, I've been contributing an occasional column called "Wobbling the Works" focused on how labor law affects union organizing. I'll still be writing on this topic once in a while, but lately my attention has been on a concept which I'll call "minority unionism," a way to describe a method of organizing that does not wait for a majority of workers in a workplace to win the legal right to bargain. This month I'm going to share some of the things that piqued my interest and pointed me in this direction.

I recently had to redo the IWW's constitution for our fellow workers in IWW Regional Organising Committees, who were tired of American misspellings of words like labour and organising. Searching through the constitution got me thinking about the idea of job branches. A job branch is a group of five or more IWW members at a given workplace who are charged with getting together on a monthly basis. The plain implication is that they would discuss grievances, come up with strategies to resolve them, and build a union presence on the job.

I am working on a project that started out as a video version of the classic IWW pamphlet A Worker's Guide to Direct Action, but has grown a bit in scope since we started. Researching the video, I saw Miriam Ching Yoon Louie speak about her book Sweatshop Warriors, which provides some excellent examples of how immigrant workers centers have helped individual workers understand their rights and organize on a variety of work and community issues. I also got the chance to interview Barbara Prear, a housekeeper at the University of North Carolina and president of UE Local 150, when she visited support staff at Swarthmore College, who have been conducting a living wage campaign for six years. The UNC union has no legal right to bargain, but has been very successful in using pressure tactics to get administrators to the table and negotiate improvements for the lowest-paid workers on campus.

I have been thinking quite a bit about ways that workers who do not have a legal mandate to bargain and have no contract can act union, using the law to augment their work. This came up because Staughton Lynd asked me to work with him on a new edition of Labor Law for the Rank and Filer at a moment when I had become particularly cynical about the potential for using labor law in organizing. I've just come back from spending a weekend with the Lynds, people from the Youngstown Workers Solidarity Club and their rank-and-filer-troublemaking cohorts from near and not-so-near places, veteran activists, and student organizers.

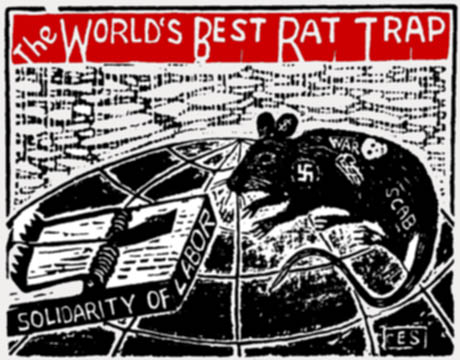

The club developed as a "parallel central labor body" to fill a void when the local central labor council could not provide sufficient support for a strike. Hanging out with these folks was the antidote for the cynicism I was feeling; not that I now have more confidence in the law, but I feel more able to look at the possibilities... A month ago I saw a documentary on the Overnite trucking strike, "American Standoff," which I reviewed last issue. "Standoff" illustrated a lot of problems that labor has not adequately confronted. How do we deal with organizing in companies that are so anti-union that they are willing to spend millions of dollars to keep workers from even getting to the bargaining table? The Teamsters' Overnite campaign, which is now on a road so difficult that it isn't clear it can be salvaged, is one of a long string of campaigns that seem to have left labor scratching its collective head, wondering what to do in the face of self-destructive upper management and backwards labor law. Clearly, the answer is not to give up. It isn't to settle for a minority clique of agitators in each workplace. It's to form meaningful, organized networks of solidarity capable of winning improvements in individual workplaces, throughout industries, and for the benefit of the international working class.

And last but not least, several fellow workers from across the water forwarded me an article on minority unionism that ran in a recent issue of The Nation. The article, by Richard B. Freeman and Joel Rogers, argues that the AFL-CIO should develop a plan for organizing that does not depend on having a majority at a workplace. The thing that was so great about getting multiple copies of this article in my inbox was the puzzlement of the non-American unionists who sent it. The way us backwards Yanks do things is absurd. Few countries do unionism the way it's done in the U.S., with the union being the sole bargaining agent of a declared majority. I think it would help if more workers I talk to knew how other places do it, and would also be good if folks outside the U.S. saw the implications of how it's done here.

So, that's the point of this column. I want to share these stories and experiences. I want to connect my fellow workers with resources that others have found useful to their work. I can't offer a recipe for success . not all of these examples will be appropriate for everyone. But smart thinking on a way forward isn't just possible, it is happening. And by developing resources to try these things out, we will give one another the confidence to turn comments like "what a good idea" into "I'm going to give that a try."