Minority Report #3

By Alexis Buss, Industrial Worker (November 2002)

In this column and at other times, I have written about a major advantage the IWW has over business unions, specifically when it comes to our practice that any worker can join and find meaning in his or her membership through organizing regardless of whether or not a majority of workers on the job have declared in some fashion that they want to bargain with the boss: Minority Unionism.

There are other advantages to the IWW -- we abide by the principle of one member, one vote. Every officer and representative in this union is elected, and the folks sitting in these seats rotate frequently. Every change in the structure of our union is voted on, including dues rates and constitutional amendments: Democracy. Our membership also tends to be very eager to engage in struggle to win better conditions. Wobblies are often the first to arrive on the picket line and the last to leave, even when the picket doesn't benefit them directly: Militancy. These elements shouldn't make us unique, but sadly often they do.

Increasing militancy and democracy can only benefit any workers' organization, especially business unions, and there are people who work quite hard for that kind of reform. But these are very limited reforms for unions that stay tamely within the limits of the labor law regime.

Since I wrote the first installment of this column, I have come to realize how troublesome the idea of minority unionism is to the business union model, particularly when it comes to jurisdictions. Let's look at the following hypothetical example:

Alice, a loading dock worker at Best Buy (an electronics superstore), is told that she must buy her own pair of safety shoes. That's legal. She doesn't want to, the safety shoes are expensive. Let's say for the sake of argument, most of her co-workers agree they shouldn't have to pay for the shoes. The policy that has been handed down is going to go into effect in two weeks.

Alice talks to an electrician who came in to run service for some new gadgetry. The electrician is an IBEW member, and tells her that if she were union, the shoes issue wouldn't happen because the union would make the company pay the cost of any safety-required clothing.

Alice calls the IBEW and says that she wants to join the union. This is crazy talk to the person who took her call. She'd need to go through the apprenticeship program and there's a big waiting list. And there's not enough work in the area to support new members. Alice hangs up the phone, bewildered by her encounter with craft unionism.

She talks to a trucker making a delivery. The trucker is a Teamster. The Teamster also tells her that making a union is a way to handle this situation. Alice calls the Teamsters and asks to join the union. Let's say in this case that we're dealing with a local that is experimenting with minority unionism, because they also have things going on at Overnite and they needed to develop some strategy that would keep a union presence on the job (please note, I'm saying this for the sake of argument -- it's not something that has actually happened). The Teamsters say, "Yes, join us."

But one of Alice's co-workers has a brother who works in the public sector, also on a loading dock, and is represented by SEIU. That worker joins the SEIU.

The UFCW, representing retail workers, gets wind of the fact that this is going on and demands the memberships of these workers, which the AFL-CIO awards them. But neither worker wants the UFCW because that union is misrepresenting the folks at the shopping market across the way. Instead they buy their own pairs of safety shoes and forget about talking union.

I know the above is a scenario of my own invention, but I think it can help to illustrate the problems that would pop up if business unions adopted any kind of minority unionism or direct affiliation program. The reason I think it would likely turn out the way I describe above -- maybe not in all cases, but often enough that it would be problematic -- is that business unionists made a decision to abandon minority unionism in 1935 when they advocated for the Wagner Act.

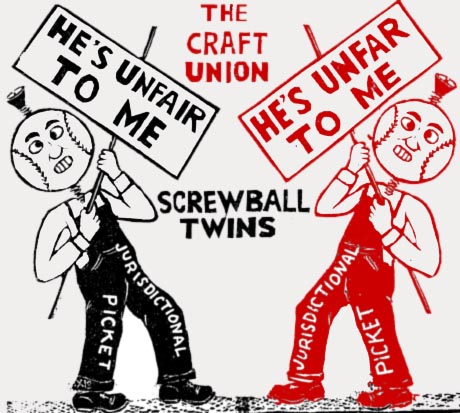

The Wagner Act -- while it allows for protections for workers engaged in minority unionism through its provision protecting concerted activity -- was welcomed by officers of business unions because, among other things, the law guaranteed exclusive bargaining rights to unions that won representation and facilitated maintenance of membership provisions like dues check-off. And the AFL-CIO takes this even further in its structure with anti-raiding and jurisdictional language, which has protected the worst of the affiliate unions by blocking workers who cannot hope to imbue democracy and militancy in a union representing them, and instead wish to throw the bums out and get a new union.

In Australia, government, chartered unions, and the bosses have carved up the work life of the country into industrial jurisdictions. Unions are given exclusive bargaining rights for industry standards like time off, pay rates, safety regulations, hours and working conditions. They have the right to bargain regardless of the density of their membership, but the outcome of the bargaining affects every worker in the industry, union member or not. When a worker becomes a member, they often do so to address particular conditions in their own shops. One worker can be a union member and use the union to agitate for his own individual interests or for the entire shop. Because of the history of American unions' fights for legal rights, I can imagine a system that apes the Australian system, but without the legal right to bargain for entire industries.

It would happen by the AFL-CIO carving up jurisdictions and agreeing that only unions with jurisdiction over an industry could take a member working in that industry. Much of this work has already been done, it has just been strayed from in these lean years. The Australian system came about because workers' activity was on the rise. Many went "union shopping," changing organizations as it suited them in pursuit of the maximum possible level of militancy. Instead of encouraging this militancy, a choice was made to control the workers by only allowing them membership in a very circumscribed manner.

An interesting side note: the Australian system isn't true industrial unionism. For instance, there is a secretaries' union. Secretaries are a necessary part of almost any industry, but instead of being part of the union that represents their industry, they are represented by a craft union. Ironically, although women overwhelmingly do the job, the union is controlled by anti-feminist men, largely because the union has very few voting members. The union does little to organize the people it represents, and even undoes the work of members looking to reform the union. The union can behave this way because it can maintain bargaining rights in spite of a very low number of actual members. So this allows a group of people who have come to be very unpopular with secretaries to exclusively represent them.

Back to the scenario of Alice, what would the IWW do? We'd get to work on the shoes issue right away. Alice would most likely first encounter either a mixed worker local (a General Membership Branch) or an Industrial District Council, an organization that helps unite all workers regardless of what industry they work in. She would be put in touch with other members, and given training and solidarity. She would learn how to organize to win demands, and how to build the union's presence on her job.

The IWW is open to all workers, and our system of industrial unions is made in order to enhance our power. The only reason to worry about which industrial union one should be in is to give ourselves the most bargaining power and job control possible .not to protect jurisdictions. The IWW opposed the Wagner Act when the thinkers who brought it into existence first thunk it up. That's because we saw the danger of asking laws to do our organizing for us, and we wanted nothing of the stifling bureaucracy, limited vision and anti-solidarity methods of the business unions.

Orienting ourselves towards building our movement this way makes us different in a very profound way. We are choosing to experiment with new methods of organizing, methods that have potential not only to succeed in winning small grievances, but in building a movement capable of making a real difference.