Perspective: Unions, OWS, & Blocking the Ports

Submitted on Tue, 12/13/2011 - 3:41pm

By Richard Meyers - This article was originally published on Daily Kos and reused under ">fair use guidelines. Fellow Worker Meyers is involved with Occupy Denver. The opinions expressed here are the author's alone.

By Richard Meyers - This article was originally published on Daily Kos and reused under ">fair use guidelines. Fellow Worker Meyers is involved with Occupy Denver. The opinions expressed here are the author's alone.

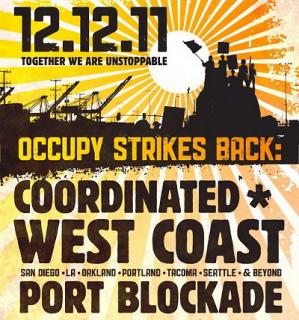

There's a debate raging over the OWS port shutdowns, and the role of unions in the shutdowns. Some believe workers have been betrayed; others claim that unions simply cannot signal their support.

Suggesting that a union does, or does not support an action like shutting down the ports (on the basis of what we've seen so far) is a gross oversimplification. In the first place, the no-strike clause has legal implications, with the result that statements of position may exist primarily to satisfy legal obligations.

Second, as we have apparently seen with ILWU 10, there may be significant differences in position and perception between local leadership and national/international leadership.

Third, all of those stating in comments on other KOS articles that they've drawn conclusions based upon what has been published ought to hold their breath; we've never before seen a global movement like OWS interact with a mainstream labor movement before. It is very likely, in spite of pronouncements, that many union leaders at the local AND the national level hadn't yet formed opinions on a one day demonstration port shutdown; many will have awaited the opportunity to assess the effectiveness of, and the public's reactions to, the day's actions.

The history of the labor movement, characteristics of the labor bureaucracy, and the success of the effort (operationally, and perceptually) will play a role in what is about to unfold.

There has long been tension between the goals and tactics of union locals, frequently as expressed in central labor councils, and leadership of AFL/AFL-CIO affiliates.

The AFL came out very strongly against actions with significant local labor support in 1919. Several central labor councils called or contemplated general strikes that year, after which the national conventions prohibited central labor councils from calling such strikes. There were two significant general strikes that year -- in Seattle, and in Winnipeg -- and many others were about to spring up. But the power in the AFL (and now in the AFL-CIO) is in the individual affiliates, and some affiliates fear losing their dues base as a result of employers voiding their labor contracts during a general strike.

The dues base is the source of power for business unions. Thus, they are sometimes willing to look the other way when companies occasionally violate labor contracts, but fear to violate contracts themselves. And nearly every business union contract has a "no strike" clause. Thus, since contracts expire at all different times of the year, general strikes have rarely happened in the United States.

It is possible that this could change -- i'll explain why below.

Union Locals and Central Labor Councils tend to be close to the rank and file. The national leadership of each union, regrettably, is not. Local labor leaders are elected. In most unions, national leadership is not elected, they're selected by a bureaucracy of delegates. Thus, it is not unusual for the interests of local rank and file members, and of national leaders, to be at odds.

What do national labor leaders want out of OWS? I surmise they want a club that they can wield against those who oppose unions. The threat of general strikes could act as such a club, especially when things haven't been going well for labor's legislative agenda. Yet OWS presents two conflicting sets of circumstances -- an extended, militant base of support, but no easy means of control over that base.

National leaders likely see the benefit of plausible deniability of not really controlling OWS when they're hob-nobbing with politicians and corporate powers. While direct control is possible over the rank and file of affiliated unions who interact with OWS, national leaders are likely to allow a slack leash, just long enough to see what comes of the OWS mobilizations.

If the AFL-CIO national affiliates (the ILWU in particular) had really not wanted OWS to attempt closing the ports, they would have sent that message in no uncertain terms. OWS would have received such a message, and understood it implicitly. Obviously, union leaders did not see any significant downside to a one day port shutdown. Why not let it ride and see where it goes?

And what of the published claim that west coast port shutdowns would hurt workers? THAT gives plausible deniability with the rank and file. If the shutdown somehow goes badly, national leaders can say, "see? We told you so!"

Thus, a perceived conflict between the ILWU national leadership, and (for example) ILWU Local 10 may be real, or it may be simply our perception. I wouldn't read too much into it.

Who's got the power in the event of differing opinions? National affiliate leadership has the ultimate say in most everything, if they choose to exercise it. But expect them to stay coy, at least for a while. They see (as all of us do) that OWS has changed the national conversation in a way that organized labor was unable to. And that is huge.

Here's why we may see appreciable change in the mainstream labor movement: in 1950, one out of three workers in the United States was union. The number in the private sector is currently about one in twelve. Mainstream labor has seen a long, steady decline. In spite of a major split in the federation that some hoped would bring new energy, there has been no immediate prospect of reversal. But while many mainstream unions are declining, the comparatively tiny Industrial Workers of the World -- the colorful, and in some circles controversial union of militant and radical rabble-rousers who call themselves Wobblies -- is gaining support and membership at a rate unprecedented since 1924.

OWS is a Wobbly sort of endeavor, with numerous characteristics ("general assemblies", horizontal democracy, emphasis on direct action, libraries for the rank and file, and adopted creative tactics -- from clogging the court system, to the silent shaming tactic at UC Davis) either explicitly borrowed from the IWW, or re-discovered organically. The IWW is the only union in the U.S. that has supported the general strike as a vital weapon against capital since its inception in 1905. AND, the one person most credited with launching OWS in Zuccotti Park (Anthropologist David Graeber) is not just an anarchist, he is also a Wobbly.

Militant rank and file of the mainstream unions and the IWW have found their place in the middle of the OWS movement. OWS fits their philosophical aspirations rather well.

So where does it go from here? Will the AFL-CIO ultimately support some form of a general strike? Labor law criminalizes most types of secondary strikes (and a general strike is the mother of all secondary strikes). So it is more than a question of tactics. Labor organizations contemplating overt support or involvement would be stepping well outside of their comfort zones.

It has happened before. The 1919 general strikes were a direct result of worker dissatisfaction after World War I. Returning soldiers, as well as the collapse of wartime labor incentives played a role. The last significant general strike in the United States occurred in 1946, immediately after World War II. Currently, two significant (and perhaps, in some ways, comparable) wars appear to be winding down. And everyone knows that veterans have been flocking to OWS.

The AFL-CIO will continue to be somewhat uneasy about working with OWS, as it has always been about working in any capacity with the IWW. But what the AFL-CIO has been doing for the past half century hasn't been working very well in the face of union busting and political hostility. Some AFL-CIO leaders must be at least thinking about alternative strategies.

So who might possibly step outside of the normal comfort zone (damning the consequences) if circumstances continue to deteriorate for workers? Local union organizations -- probably -- in some cases. This is because some local memberships are radical, and increasingly so. National affiliate leadership, not so likely -- but they won't tip their hand until it suits them. Even with a few leaders open to new ideas, it seems likely that the stodgy old AFL-CIO will revert to form, opposing radical innovations and preventing any sort of metamorphosis.

Thus, circumstances fertile for rebellion might conceivably exist not only against the economic system, but against national labor leadership as well.

In conclusion, i contend that the union roots of OWS are much broader and deeper than most observers realize. There is no reason in the world to turn against OWS on the false basis that OWS doesn't respect workers' rights. OWS is all about workers' rights.

The really big question is: how far will national leaders of business unions go for the workers?