Less Time for Work, More Time for Life!

This article appeared in the June 2002 issue of the Industrial Worker.

Boston-area Wobblies have kicked off a campaign for a shorter work week, distributing over 2,000 flyers demanding "Less Time For Work, More Time for Life!" beginning at May Day events and culminating with a May 11 panel discussion on the fight for a shorter work week.

A follow-up meeting will develop plans for future events, and launch efforts to build a broad coalition around the issue of shorter hours.

A follow-up meeting will develop plans for future events, and launch efforts to build a broad coalition around the issue of shorter hours.

Marconi Almeida, a community organizer with the Brazilian Immigrant Center's Workers Rights Project, noted that in Brazil all workers were legally entitled to a month's paid vacation each year, as well as paid medical leave and other benefits unavailable to most U.S. workers. "In a world economy becoming ever more oppressive," Almeida noted, workers must organize and be prepared to strike both to hold onto the rights they presently have and to win back a larger portion of our lives for our own purposes.

Industrial Worker editor Jon Bekken pointed to International Labor Organization statistics showing that U.S. workers now put in the longest hours in the industrialized world. Indeed, while workers in the rest of the world have been fighting for and winning shorter hours, U.S. workers find themselves working ever-longer hours. The average Australian, Canadian or Mexican worker now puts in about 100 hours less on the job; our Brazilian and British fellow workers work 250 hours a year less than we do.

Immigrants, single mothers and the poor often work the longest hours, forced to take on two or three jobs just to eke out a meager living. Betty Reid Mandell, a founder of the welfare rights organization Survivors Inc., spoke of the implications of the continuing attacks on women forced to turn to the welfare system to support them in the work of caretaking. Ignoring the long hours required to raise children, U.S. government policy is to force these women into the paid workforce, where they find themselves in low-paying jobs, reliant on food pantries and overcrowded homeless shelters to survive.

Mandell contrasted the brutality of this approach with the widespread recognition in the 1970s that the means existed to provide a decent livelihood for all -- embodied not only in French sociologist Andr Gorz's proposal for a universal 20-hour work week, but also in U.S. President Richard Nixon's 1972 proposal for a guaranteed annual wage.

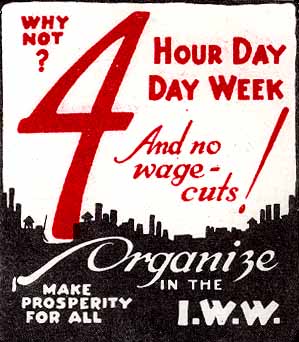

For more than 60 years, Bekken pointed out, the IWW has demanded the 4-hour work day. While this position is often seen as utopian today, when the IWW adopted it the American Federation of Labor was officially committed to the 6-hour day, which several unions had won in their contracts, and the U.S. senate (hardly a radical body) had overwhelmingly passed legislation to establish a legal 30-hour work week.

Instead, while working hours have been dropping around the world for the past 50 years, U.S. workers today are working longer hours than they did 30 years ago. Automation, speed-up and other factors result in productivity doubling every 25 to 30 years. Where did that increased productivity go? Far from living better, average wages (adjusted for inflation) are about the same as they were 25 years ago -- a statistic that masks the fact that a handful of workers are doing much better, while most have seen their wages actually fall. And we're not putting fewer hours in on the job either; in fact, we're working longer and harder. And in the current economic recession -- which the newspapers are desperately trying to persuade us is an economic recovery -- the situation is getting worse, Bekken said. Since November, average weekly overtime in manufacturing has increased even as employers slashed 38,000 jobs. Workers at companies that have laid off thousands of workers are now pressured to put in up to 20 hours a week of overtime. Even eliminating overtime would create over a half-million jobs, Bekken noted, most of it in the very industries where unemployment is highest.

Gary Zabel, co-chair of the Boston Coalition Of Contingent Academic Labor (which organizes "part-time" and temporary faculty), discussed the implementation of the 35-hour week in France as an example of the pitfalls of trying to reduce working hours within the constraints of the present economic system. While employers were forced to accept demands for shorter hours, they were able to reshape the legislation to permit employers to speed up the pace of work and make workers put in up to 44 hours a week during busy periods without overtime premiums (to be made up later during slack periods). "We can not meaningfully reduce work time if we accept the logic of capital," Zabel concluded; rather we need to "instill the habit of resistance" and build a movement to overturn the entire capitalist system.

Zabel's remarks touched off a discussion over the effectiveness of European efforts to cut the work week, in which shorter hours activist Anders Hayden argued from the audience that despite serious problems with the implementation of shorter hours, surveys had found that French workers believe their "quality of life" has improved with the 35-hour week, though few believe their life on the job has improved.

Several comments pointed to the need to pay close attention to the reality of work life on the job. Many "part-time" workers are actually working two or three jobs -- putting in 60 or 80 hours a week on the job, even though they show up in official statistics working 20 or 30 hours. Almeida noted that many Brazilian immigrants find themselves working much longer hours in the United States than they did at home. In Brazil, kitchen workers work no more than 44 hours a week; in the U.S. it is not uncommon to find kitchen workers putting in up to 80 hours a week.

Almeida also urged the audience to press the government to extend the 245i visa program, allowing undocumented workers to legalize their status. This is necessary to enable these workers to fight for rights that Brazilians take for granted (such as shorter hours, unlimited unemployment compensation and three months' paid maternity leave) but are not available to workers in the United States, Almeida said. After the program, a Brazilian woman noted that the large numbers of workers in the informal sector are excluded from many of these benefits.

Brazilian Immigrant Center Executive Director Fausto Mendes da Rocha pointed to the intense pace of work in the United States. Brazilian workers have lost ground in recent years as a result of privatization and economic "reforms," he said. International solidarity will be needed to turn back "the American model" of relentless toil on the job and make possible an effective fight for shorter hours.

The fight for shorter hours is an issue that manifests in many different ways, from mandatory overtime to jobs with no fixed hours where often relatively well-paid workers are expected to work 60 or more hours a week. On the higher end of the pay scale, U.S. airline pilots can be required to work 16-hour shifts, while medical doctors are sometimes required to put in 36- or 48-hour shifts. For full-time workers, 10- and 12-hour shifts are increasingly common.

Workers' bodies are collapsing under these brutal labor regimes, with 1.8 million workers a year contracting repetitive strain injuries such as carpal tunnel syndrome.

Meanwhile, one in ten U.S. workers is unemployed or underemployed. Wages remain stagnant, and benefits are under increasing attack. And crackdowns on immigrants and welfare recipients threaten to pull many more workers through the collapsing social safety net.

"Welfare has always been linked to work," Mandell noted, helping to maintain a reserve army of potential workers. When employers want to bring down wages they slash welfare benefits, forcing women to scramble for any job they can find. Even as unemployment is skyrocketing, a new Bush administration proposal would require welfare recipients to put in 40 hours a week of unpaid workfare labor.

A successful campaign for shorter hours could reduce unemployment, create safer workplaces by reducing fatigue, strengthen our communities, and, most importantly, enable us to reclaim our lives. "Our time is our life," Bekken noted. "The time we spend at work is not our own, and far too much of it is squandered on useless production, the support of parasites, the construction of the means of our annihilation, and so forth."

While attendance at the May 11 forum was modest (many more people attended a May Day presentation on the IWW's fight for the four hour day), the Boston Area General Membership Branch has established contact with several local organizations interested in the issue, and is working to build a broad-based coalition of environmental, feminist immigrant, welfare rights and labor organizations to press the fight for shorter hours.

Wobblies in other parts of the country have also begun working around this issue, and we hope to see a discussion at the 2002 General Assembly about ways we can coordinate efforts to build a truly international struggle for a shorter work week.